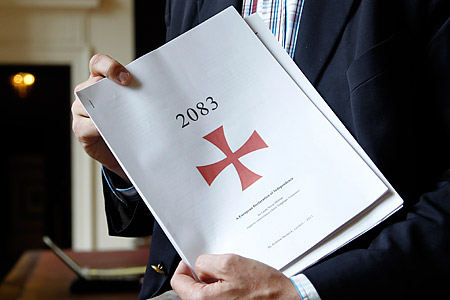

A member of Belgium's Flemish right wing Tanguy Veys poses with a part of the manifesto written by Anders Behring Breivik, July 27, 2011. (Photo: Francois Lenoir / Reuters)

Anders Behring Breivik’s massive, 1,500-pg “2083” manifesto carries within it many odd and jarring tidbits, but nothing piques curiosity more than the Norwegian terror suspect’s obsession with the Knights Templar, a militant-monastic order that participated with bloody effect in the medieval Crusades. Breivik — who is accused of orchestrating the shocking terror attacks that hit Norway last Friday — styles himself as a leading figure in a resurrected chapter of the Knights Templar, invoking the title “justiciar,” a long-forgotten term that, at this point, has more place in contemporary fantasy fictionthan real life.

But, judging from his manifesto, Breivik was deathly serious about his role and claimed that he along with around a dozen others restarted the holy order in London 2002 to turn back the supposed advance of Islam across the West. Breivik’s agenda was not merely nationalist, but pan-European. With the iconic red-cross raiment of the Knights Templar as its frontispiece, the manifesto calls for the redemption and defense of all Christendom. Breivik writes:

The time for armed resistance has come. [The] Knights Templar on behalf of the free peoples of Europe, hereby declare a pre-emptive war against the cultural Marxist/ multiculturalist regimes of Western Europe.

To be fair, the mandate of the original Knights Templar wasn’t altogether that different. The order came together in 1120 around the fabled site of Jerusalem’s Temple of Solomon — what was then actually al-Aqsa mosque, fallen into Christian hands after the First Crusade captured Jerusalem in 1099. The Knights were an elite fighting unit sworn to defend pilgrims and repulse infidels. In the centuries since it was formed, many, including Breivik, have eulogized the supposed piety and asceticism of the Knights Templar, but the order was swiftly accumulating vast donations of gold and tracts of land across Europe and stretches of the Levant. They were bolstered by the political support of a prominent French cleric, Bernard de Clairvaux, who made this invigorating declaration to them in 1136:

Go forward in safety, knights, and with undaunted souls drive off the enemies of the cross of Christ, certain that neither death nor life can separate you from the love of God… repeating to yourselves in every peril: “Whether we live or die we are Lord’s.” How glorious are the victors who return from battle! How blessed are the martyrs who die in battle!

Swap out a few of the terms (say, that bit about the cross of Christ) with others, and you could easily arrive upon the words of a chorus blaring alongside the grainy footage of an al-Qaeda training video. Breivik, though, is insensible to the irony. In his manifesto he says he and his Knights will always choose “martyrdom before dhimmitude” — the latter a term in popular use among Europe’s far-right, signifying the state of affairs when non-Muslims must live under shari’a law. (Separately, in a macabre PR-bid to win local support, a Mexican drug cartel has also called itself the Knights Templar.)

(SEE: Top 10 Elite Fighting Units.)

The Knights Templar, of course, failed. After cementing their reputation with a number of stirring victories in the Second and Third Crusades, the Order had sustained itself for years off the significant taxes it extracted from the Jews and Muslims living miserably under its watch and spent a considerable amount of its energies not only squabbling with rival Muslim states, but other Crusader kingdoms as well. But by the end of the 13th century, they and the bulk of the Crusaders had been driven out of the Holy Lands after a series of withering defeats at the hands of Muslim armies. The remaining Knights Templar abandoned their holy temple, and slunk back to the island of Cyprus, which for a time, they ruled almost in entirety. The order’s real demise, though, didn’t come with the swish of a Saracen scimitar, but through the plots and intrigues of enemies within Christendom. By 1312, the Knights Templar were dissolved, their key leaders tried and burned at the stake for heresy.

This fiery end is the subject of considerable pop cultural fascination, and has spawned myriad conspiracy theories and myths that have kept the Order well remembered up to this day. Historically, though, some in the Knights Templars ranks were swallowed up into another ex-Crusading monastic faction, the Knights Hospitaler, which was encamped primarily on the isle of Malta. In his manifesto, Breivik encourages his fellow travelers to visit Templar/Hospitaler sites in Malta. For centuries, the Hospitalers behavior there was tantamount to that of a piratical rogue state, preying on Mediterranean shipping and amassing a small army of captured slaves until the French under Napoleon seized Malta in 1798 and snuffed out the archaic, corrupt faction that had held it.

But the Templars’ ritual and symbolism has lived on in another institution: that of the Freemasons, who also place the Temple of Solomon at the heart of their cloistered mysteries. One of the more distributed pictures of Breivik since the attacks show him in what appears to be the garter of a Freemasonic order. This makes sense: Depending on the rites practiced in certain lodges on both sides of the Atlantic, one can still attain the status of a Knight Templar within the community of the Freemasons.

In an interview with TIME’s Valerie Lapinski, Susan Sommers, a professor at St. Vincent’s College in Pennsylvania who has researched 18th century Masonic movements, warns against conflating Breivik’s crusading zeal with what the mainstream of freemasonry purports to teach:

I’m sure the Freemasons don’t want any more connection with this madman than has already been made… Freemasonry is a religiously tolerant movement, and has been since the time of the early European Enlightenment. It is a movement grounded in self-improvement and moral philosophy. All Masonic degrees and orders have as their mythological background either a Biblical or historic setting–very like a stage for a play… For many of the “Higher Degrees,” such as, for example, the Knights Templar, the setting is the Crusades of the 11th-13th centuries. Of course, this is all meant to be allegorical, and is meant to instruct initiates on Christian virtues–which, by the way, are shared by most of the world’s religions.

Breivik’s appropriation of the Knights Templar proved to be far worse than allegory. The order flourished at a dark, bloody moment in human history and — Dan Brown novels and Indiana Jones flicks notwithstanding — has surfaced again at another tragically grisly chapter.

Ishaan Tharoor is a writer-reporter for TIME and editor of Global Spin. Find him on Twitter at @ishaantharoor. You can also continue the discussion on TIME‘s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIMEWorld.