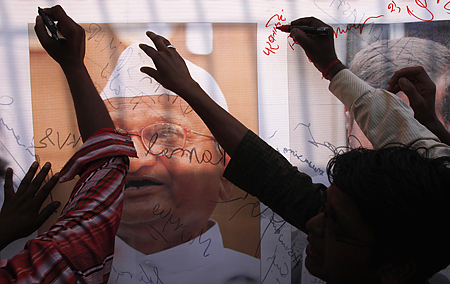

Supporters of veteran Indian social activist Anna Hazare sign a banner with a portrait of Hazare outside the Tihar jail in New Delhi, August 17, 2011. (Photo: Adnan Abidi / Reuters)

The anti-corruption activist Anna Hazare agreed to step out of jail late last night, after reaching an agreement to hold a 15-day protest fast instead of the 30-day strike he originally planned. That compromise may not be enough, though, to restore the damaged credibility of the Indian government, which has struggled to answer the public’s mounting frustration and disillusionment with its efforts to fight corruption.

Thousands of Indians gathered in the streets of New Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and smaller cities in between on Wednesday to vent their growing fury against the government’s failure to act decisively against corruption. The trigger this time — there was a wave of similar anti-corruption protests earlier this summer — was the “preventive detention” of an aged activist named Anna Hazare in New Delhi’s Tihar jail. He was arrested along with 2,603 of his followers, who had all planned to defy local police orders restricting Hazare’s planned hunger strike and mass demonstration. Facing public and political criticism, officials backed down and agreed to release Hazare from jail but would not lift all the conditions — key among them his demand to continue his protest fast for a month. Negotiations began, but the old man in the homespun cotton kurta and cap refused to leave his jail cell, and people poured into the streets. The ones who gathered today were not hard-core activists courting arrest; they were ordinary Indians — teachers, students and office workers — outraged not just at corruption but at the government’s attempt to limit their constitutional right to protest against it.

Their anger has little to do with the Lokpal Bill, the issue around which Hazare has organized his movement earlier this year. He wants the government to set up an independent ombusdman with the authority to investigate corruption at every level, even the Prime Minister. He went on a hunger strike for that cause in April, and more or less won — the government agreed to form a committee to draft a bill. The proposed legislation they came up with was too weak, Hazare said, so he planned another mass protest and indefinite fast. That’s when Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and his cabinet dug in its heels. During Monday’s Independence Day speech, Singh alluded to the Lokpal, saying that no “magic wand” could simply make corruption disappear. Today, in a speech in Parliament, Singh criticized Hazare for trying to usurp the deliberative political and legislative process with the public drama of a hunger strike.

“The question is, who drafts the law and who makes the law? I submit that the time-honoured practice is that the Executive drafts a Bill and places it before Parliament and that Parliament debates and adopts the Bill with amendments if necessary. … As far as I am able to gather, Shri Anna Hazare questions these principles and claims a right to impose his Jan Lok Pal Bill upon Parliament. I acknowledge that Shri Anna Hazare may be inspired by high ideals in his campaign to set up a strong and effective Lok Pal. However, the path that he has chosen to impose his draft of a Bill upon Parliament is totally misconceived and fraught with grave consequences for our Parliamentary democracy.”

Singh does have support for this position. India already has strong, if poorly enforced, anti-corruption laws and it already has other independent agencies, like the Comptroller and Auditor General’s office — whose scathing reports began the debate over corruption last year, beginning with the Commonwealth Games fiasco and continuing with a slowly evolving telecom scandal, in which two ministers have already resigned. It’s not clear that the Lokpal bill would be much of an improvement. It’s also hard to imagine how the world’s largest democracy would function if it gave way every time a prominent protestor demanded a new piece of legislation.

However elegant his legal reasoning, Singh completely missed the larger political point. The opposition Bharatiya Janata Party wasted no time in reminding him. Arun Jaitley, a BJP leader, declared passionately that Hazare’s protest isn’t about the Lokpal Bill at all — it’s “a symbolic battle against corruption.” As Jaitley lit into the Prime Minister and his Congress Party for hiding behind police regulations and ignoring substantive concerns about corruption, Singh seemed to visibly shrink into his chair. Singh has always been considered above reproach personally, but that may no longer be enough to maintain his credibility. He now has to offer more than tough talk. (“Corruption is a big obstacle in national transformation,” he said during his Independence Day speech on Monday.)

His first real test will come with the accusations leveled against Sheila Dixit, the chief minister of Delhi and a longtime associate of Sonia Gandhi, the Congress Party president. The most recent auditor general’s report on the Commonwealth Games, released in early August, faults Dixit for not reining in the Games’ organizers and says that she was ultimately responsible for a large chunk of the budget. The chief minister of another state was asked to resign after he was named (but not convicted of any crime) in a Mumbai real estate scandal, but so far, Singh, Gandhi and the Congress Party have stood firmly behind Dixit, refusing to entertain vehement calls by the opposition for her to resign.

As India prepares for two more weeks of protest, the government’s symbolic battle against corruption may have already been lost.