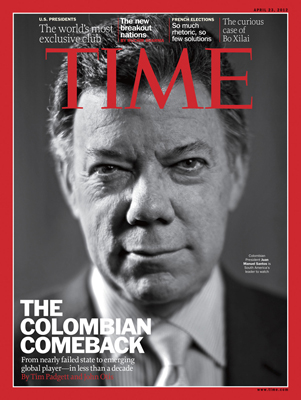

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos will host the sixth Summit of the Americas this weekend, April 14 to 15, in the Caribbean city of Cartagena. The hemispheric gathering marks a comeback for Colombia, which is emerging from half a century of crippling guerrilla, drug and political violence and is making a serious bid to be Latin America’s new economic and diplomatic player. The center-right Santos, 60, recently sat down at the Casa de Nariño palace in Bogotá with TIME International Editor Jim Frederick, TIME’s Latin America bureau chief Tim Padgett and its Colombia reporter, John Otis, to discuss the summit, the region’s decreasing dependence on the U.S. and Colombia’s chances for a peaceful end to its long conflict.

(READ: This week’s magazine story on Santos and Colombia’s comeback)

To everyone’s surprise, you recently called for a discussion of legalizing drugs as a way to address the world’s largely failed drug-war strategy. Will this be debated at the summit — and do you see any way of getting the U.S. onboard?

SANTOS: I want the world to discuss if we are doing the correct thing or if there are possible alternatives that are less costly [in terms of lives and interdiction resources]. I hope the summit endorses the proposal. I think the U.S., too, is willing to discuss the issue, and I think this is a very important and big step in the right direction.

After being considered a nearly failed state, a near narcostate, only a decade ago, is this summit a coming-out party for Colombia — not just as a nation rebounding from almost 50 years of conflict but as a new hemispheric leader as well?

Yes, I think this [summit] coincides with many processes that have given Colombia a new and much more important position. We were for many decades signaled as a nonviable state, as the champions of kidnapping, drug trafficking, murders, violations of human rights; and for many years people didn’t even want to come to Colombia because they were afraid. We have been changing this reality. Today the world is understanding that Colombia is one of its most dynamic democracies and economies. Who would have thought just a few years ago that the spread on our sovereign bonds would be lower than Japan, Italy, France and competing with the U.S.? This is completely out of anyone’s imagination.

Yet there are big concerns that Colombia’s hard-won security is backsliding: the country’s Marxist guerrillas, the Revolutionary Armed Forces, or FARC, are regrouping and making fresh attacks and new bandas criminales are expanding.

I’ll be the first to recognize that we are winning but we have not won yet. We have a long way to go still. The FARC is still active, but they’re weaker and weaker, that’s why they are now [focused] on terrorist acts [to] show the country and the world that they are still alive. That’s what they want — but that’s a demonstration of their weakness. The bandas are a direct inheritance from the [right-wing, now disbanded] paramilitary groups that [like the FARC] were also dedicated to drug trafficking. With them there is no room for negotiations. They are criminals, and we will be as effective against them as we were in dismantling Colombia’s once impenetrable, all-powerful drug cartels.

The FARC just released the last of its military and police hostages as a goodwill gesture. Does that bring Colombia closer to peace negotiations — and do you believe you’ll be the President who ends the 48-year-old conflict?

I am always open to a political solution to this conflict, provided they demonstrate that they can sit down and negotiate in good faith. Which has not happened yet. I certainly hope [to be the President who ends the conflict]. But the worst thing I could do is be in a hurry. I have to wait for the correct circumstances, and for that I have to be patient.

(VIDEO: Interview with Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos)

How much of a debt does Colombia owe the U.S. and its $5 billion Plan Colombia? Is it also fair to say you’ve distanced Colombia from the U.S. somewhat since taking office?

No, I’m not interested in distancing myself from the U.S. We owe tremendous gratitude to the U.S. I think Plan Colombia is probably the most successful bipartisan foreign policy initiative in the recent history of the U.S., and we’re proud to be its beneficiaries. But it also represents only 4% of what we ourselves invest in our security.

Is it more accurate to say, then, that Colombia wants to be an interlocutor between the U.S. and Latin America? Should Washington view you in that role as a more valuable partner?

Yes, the U.S. has told me they welcome our new good relations with our neighbors, and my neighbors value my good relations with the U.S. We do see ourselves as a bridge between the U.S. and the [Latin American] countries with which the U.S. doesn’t have particularly good relations now.

How would you describe your personal relationship with President Obama?

We have a good personal relationship — at least I hope so after [my U.S. alma mater] Kansas beat North Carolina [the team Obama favored] in the NCAA tournament last month. We have a good chemistry.

Is the recent agreement you brokered with Cuba — to not invite it to this summit but to push for its inclusion in future summits — an example of the “bridge” role you describe?

I believe very much in the value of putting your face to problems. That’s what I did with [left-wing Venezuelan President] Hugo Chávez: We used to insult each other on a daily basis [when I was Defense Minister]. But I decided to confront the problem as head of state, and I said, Let’s respect our differences. I simply could have said to the media, [Cuba] is not coming [to the summit]. But I think the fact of going [to Havana] and explaining [the situation], [President Raúl Castro] valued that.

Do you fear what’s on the horizon next door in Venezuela as a result of President Chávez’s battle with cancer?

What I hope is that Hugo Chávez doesn’t die, because at this moment he is a factor of stability. What would hurt Colombia and the whole region more is an unstable Venezuela.

Christopher Morris / VII for TIME

You just secured a free-trade agreement with the U.S., yet one of the concerns hanging over this summit is Washington’s shrinking influence in Latin America. Is the inter-American ideal still relevant in the 21st century?

The U.S. should value more the importance of Latin America — of its strategic long-term interest for the U.S. The more they look south again, the more we will look north again. We need each other, but it’s a two-way street now.

Some feel Latin America is looking more to Asia now, especially China. Latin America is enjoying an economic boom and more rapid development, but are its economies, including yours, depending too much on commodities exports and not enough on building its manufacturing and value-added sectors?

We are struggling to not have this high dependence on commodities and we’re increasing investment in manufactured goods. But you also have to ask, How is the world going to be fed with 2 billion more Chinese and Indians in the future? Those commodities become a very important player.

Your more conservative predecessor, Alvaro Uribe, is credited with restoring security to Colombia, but he’s criticized for not addressing the root social causes of Colombia’s conflicts. Do you feel you’re addressing them adequately now?

Yes, especially our inequality of resources. We’ve achieved a constitutional reform previously considered impossible, to distribute mining and oil revenues much more evenly, a sort of affirmative action to the poorest regions. And land restitution and title for peasants displaced by the violence: this is a real agrarian revolution. And we are about to present to Congress a tax reform geared toward making our country more equitable.

Are you showing the Latin American right that it too, like much of the Latin left today, can practice a more centrist “third way” between capitalism and socialism?

The more I apply the principles of the third way, the more convinced I am that this is the correct way: use the markets as much as possible and the state as much as necessary. Sometimes I say to some of our neighbors, You’re choosing [left or right] extremes that will not work. This is the best approach for Latin America. Governability has been the key to [Colombia’s] success, getting people to agree on things. Polarized societies are a perfect recipe for failure.

Uribe and his “Uribista” supporters, however, have become some of your most vocal critics — and they say you’re an opportunist who has betrayed the conservative principles you backed under Uribe.

That’s a small minority, and they are being very shortsighted: they should have read [the more moderate policy positions] I’ve been writing for the past 20 or 30 years. About being conservative as Defense Minister, I was simply doing my job. And modesty aside, I was the most successful Defense Minister this country has had in its last 50 years. I have not given [Uribe] any reason to be such a staunch critic.

Do you see Colombia as a model for how Latin America can escape the lawlessness and inequality that still plague it?

We’re the oldest democracy in Latin America, and I think we are [rediscovering] a respect among Colombians for rules that give us the opportunity to develop in a collective way. What I know is that when you ask people in the U.S., Europe and Japan today if their kids will have a better future, they say no. In Colombia they’re saying yes. I think that’s extremely important in any society.

MORE: Waiting for the FARC: Colombia’s President Santos Tells TIME He Won’t Move Too Fast